2017 PRIZE

The 13th Veronica Rudge Green Prize in Urban Design recognizes the High Line as exemplar for the complex coordination of creative professionals, philanthropists, and policy makers by deeply committed community advocates.

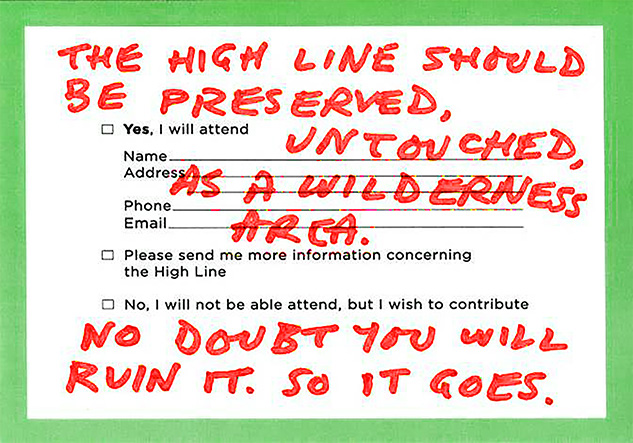

West Chelsea was transforming from a neighborhood of meat–packers, leather clubs, NYC counter–culture, and NYCHA housing projects into one with white collar office workers and developer speculation. A historic, elevated rail line was in the way and had to go. After countless public meetings, fundraising events, celebrity endorsements, guerrilla marketing strategies, and design competitions, Friends of the High Line slowly shifted public opinion from antipathy to enthusiasm.

The High Line is now both a nonprofit organization and a public park on the West Side of Manhattan. Through their work with communities on and off the High Line, they’re devoted to reimagining the role public spaces have in creating connected, healthy neighborhoods and cities.

Built on the same rail line, the High Line was always intended to be more than a park. You can walk through gardens, view art, experience a performance, savor delicious food, or connect with friends and neighbors-all while enjoying a unique perspective of New York City.

About the Project

The High Life

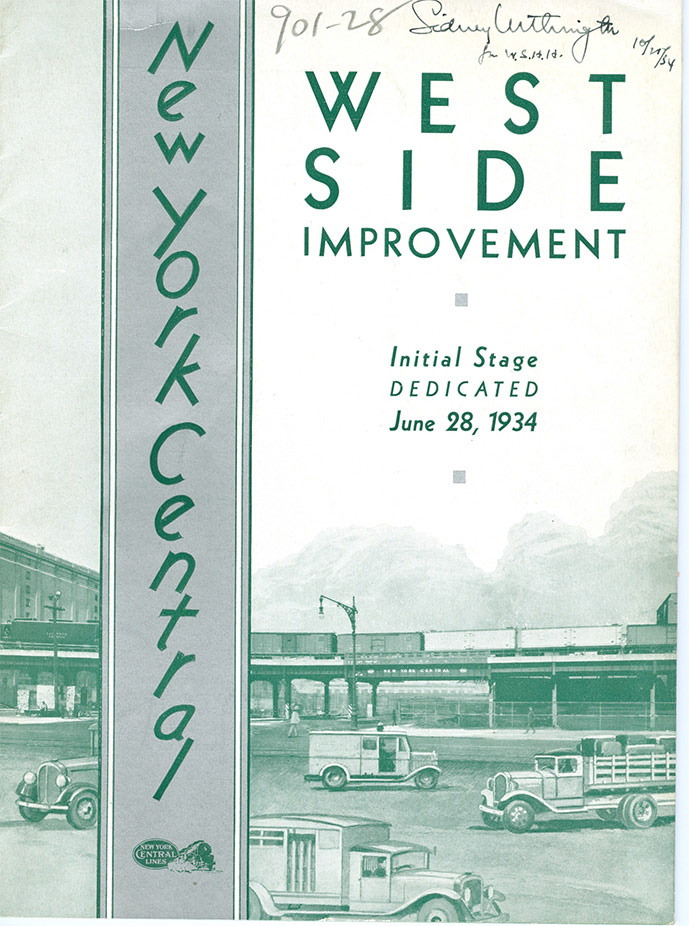

By the early 1900s, the West Side of Manhattan had become a dangerously congested industrial hub with a hectic and overlapping mixture of freight-lines, trucking-routes, and pedestrian-flows. After more than 436 people were killed and 1,500 maimed by freight trains, Tenth Avenue was dubbed “Death Avenue”, and the city responded by hiring mounted patrols, “West Side Cowboys,” to guide trains through the area. In 1908, a group of concerned citizens formed the League to End Death Avenue and lobbied the city for change. The story of Manhattan’s West Side is one of continual reinvention; cycles of redevelopment and renewal within which the High Line has played a pivotal role at various times in history. When the West Side Improvement Project was proposed in 1929, the High Line was hailed as transformational. The questions of the time were how- not if – to re-envision the West Side, and what role this rail infrastructure would play in that process. Though it was clear in the late 1920s how an infrastructural innovation like the High Line could amplify economic growth and support a more vibrant public realm for the area, by the late 1990s, this kind of creative thinking was in short supply.

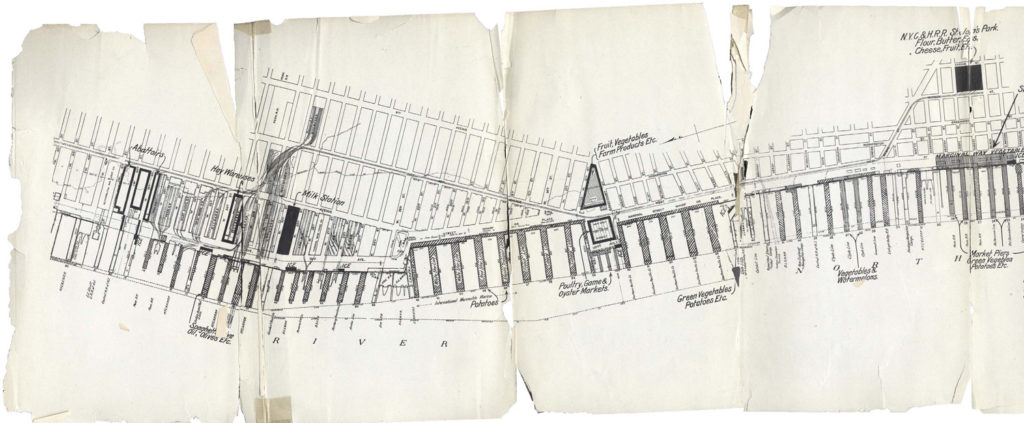

Even before the High Line, the Manhattan’s West Side served as New York City’s central hub for food and freight. This map from 1912, highlights the specialized markets served by freight boats and the New York Central Railroad

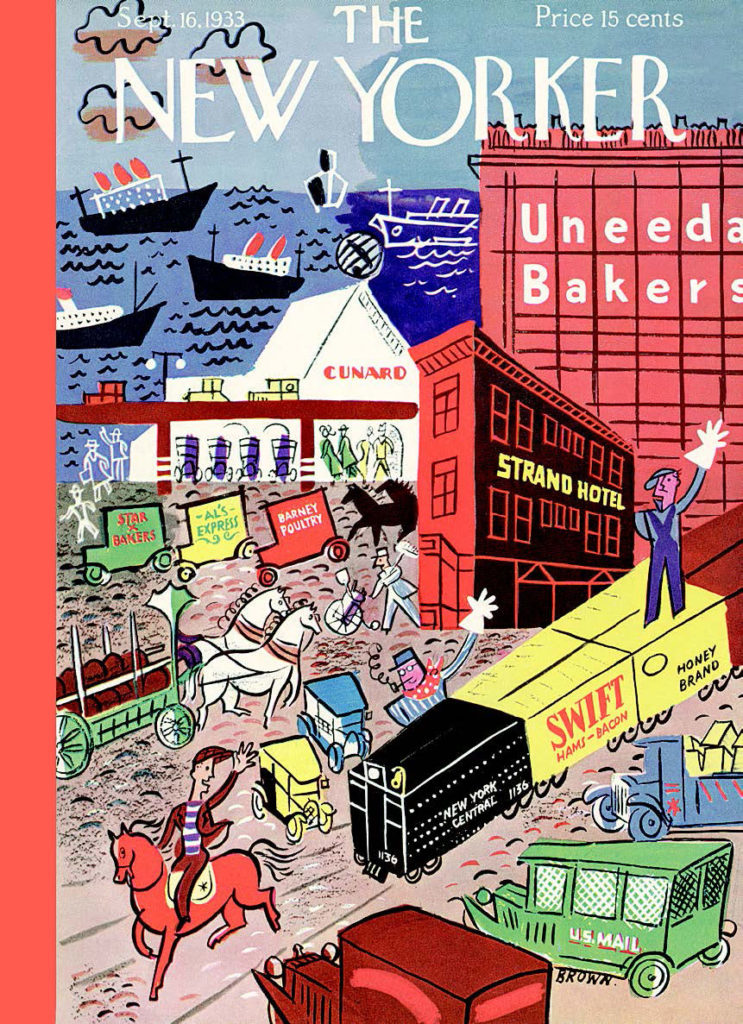

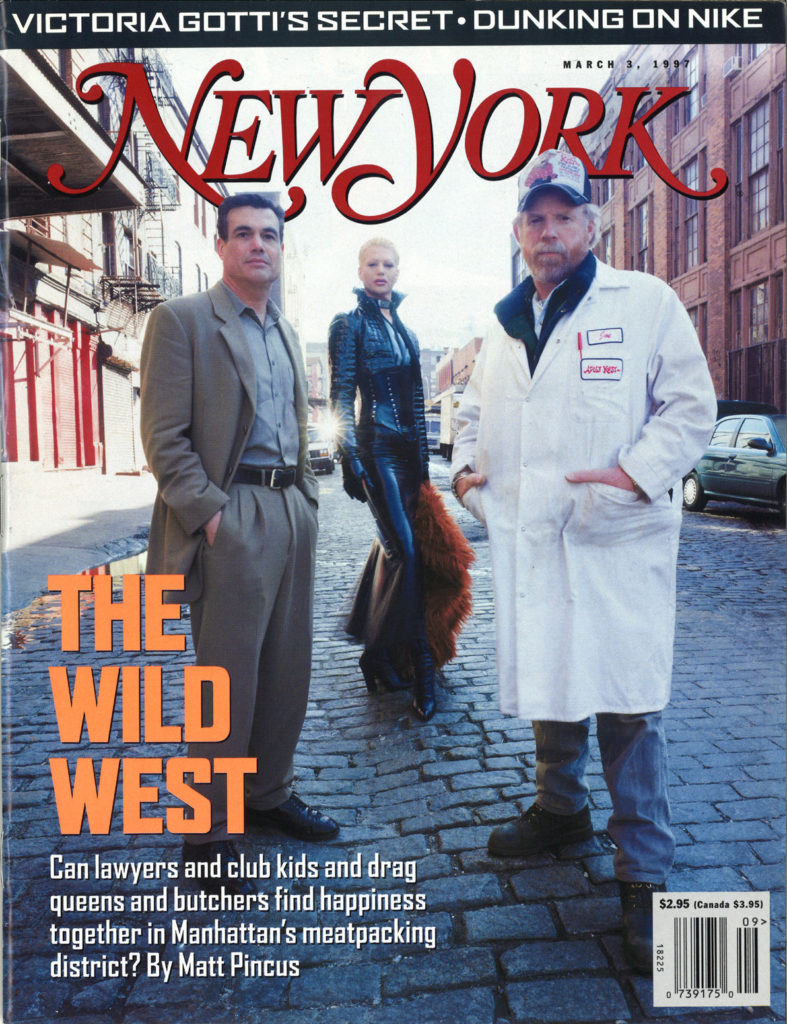

The New Yorker cover from 1933 and the New York Magazine cover from 2007 tell a remarkably similar story of renewal and regeneration in which the High Line has, and continues, to play a central role.

Along with the proposal for the West Side Highway, the elevated rail became the first major project of the New York City’s West Side Improvement plan.

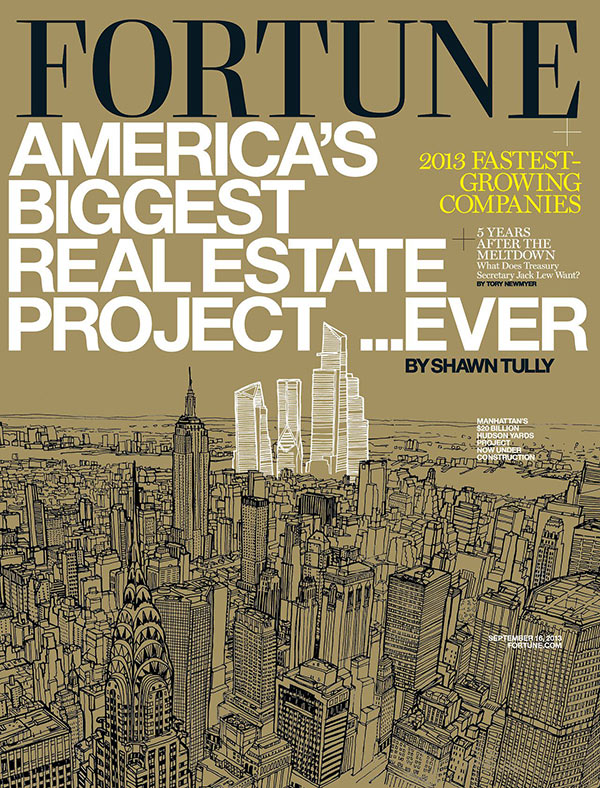

Though impressive, the positive and negative effects of these developments have been unevenly distributed. While developers have reaped the rewards of skyrocketing property values and the broader public have gained a new open space, low- and middle-income communities have faced rising rents, increasing many times faster than in other neighborhoods in the city.

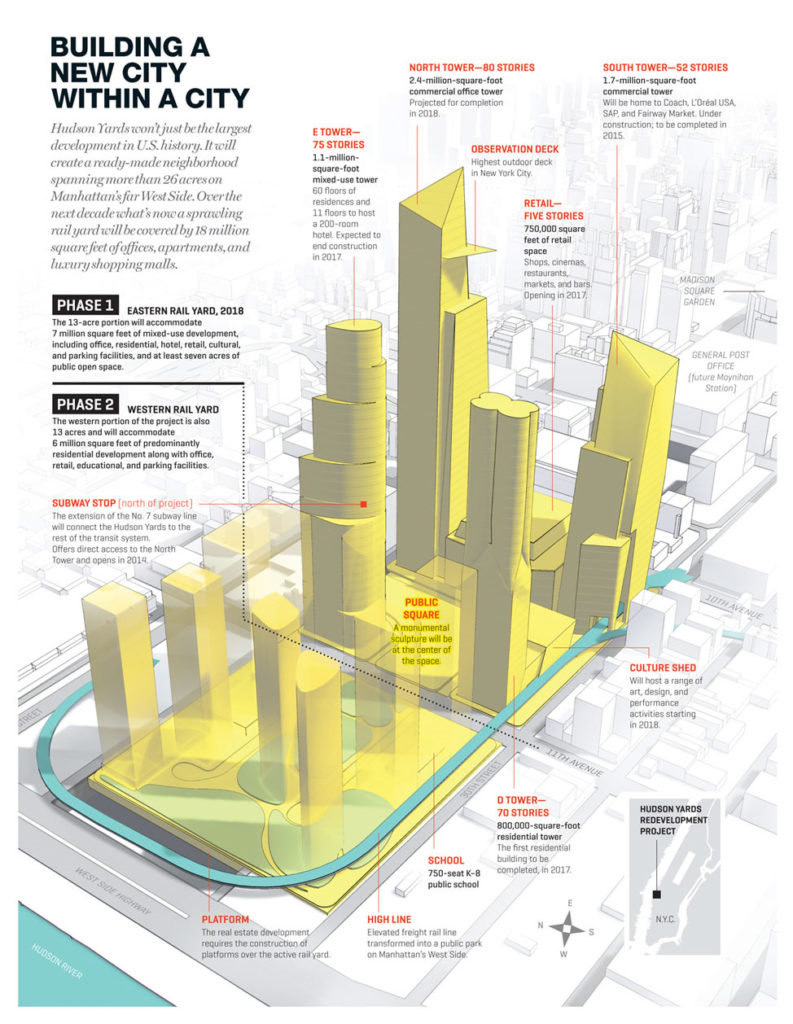

One third of the High Line passes over, and through, Hudson Yards. This development project, by square footage, is projected to be the largest private real estate development in the history of the United States.

Dissonance

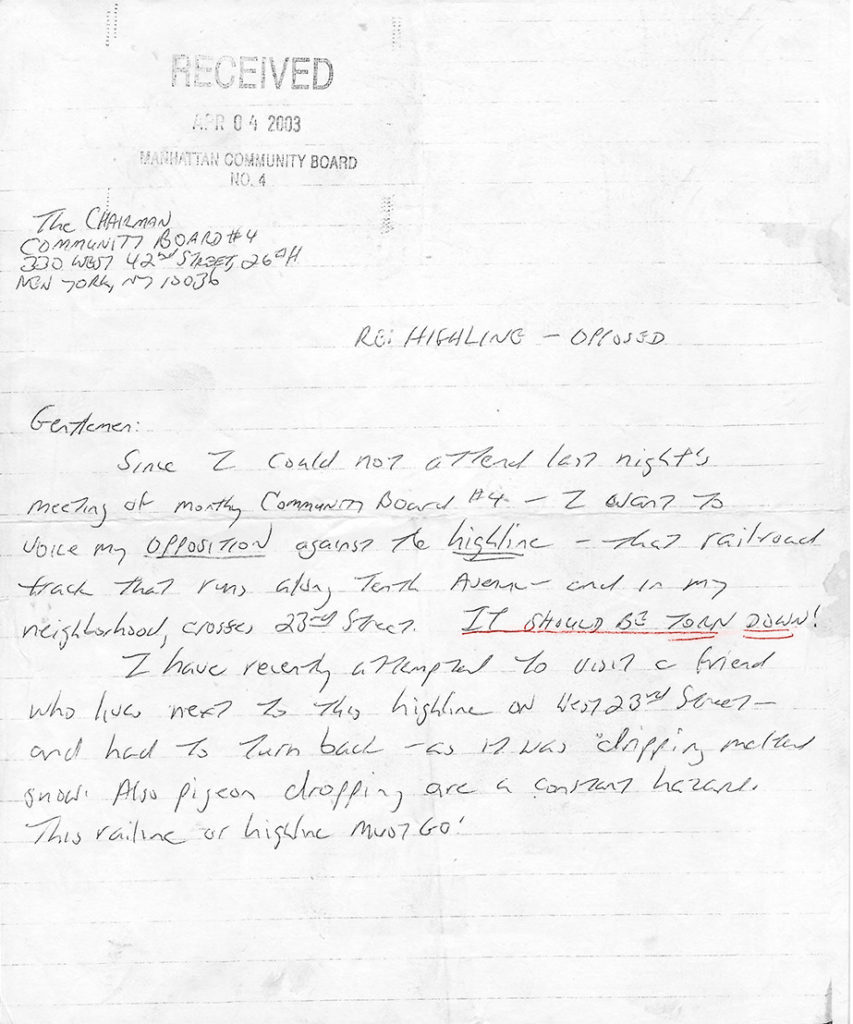

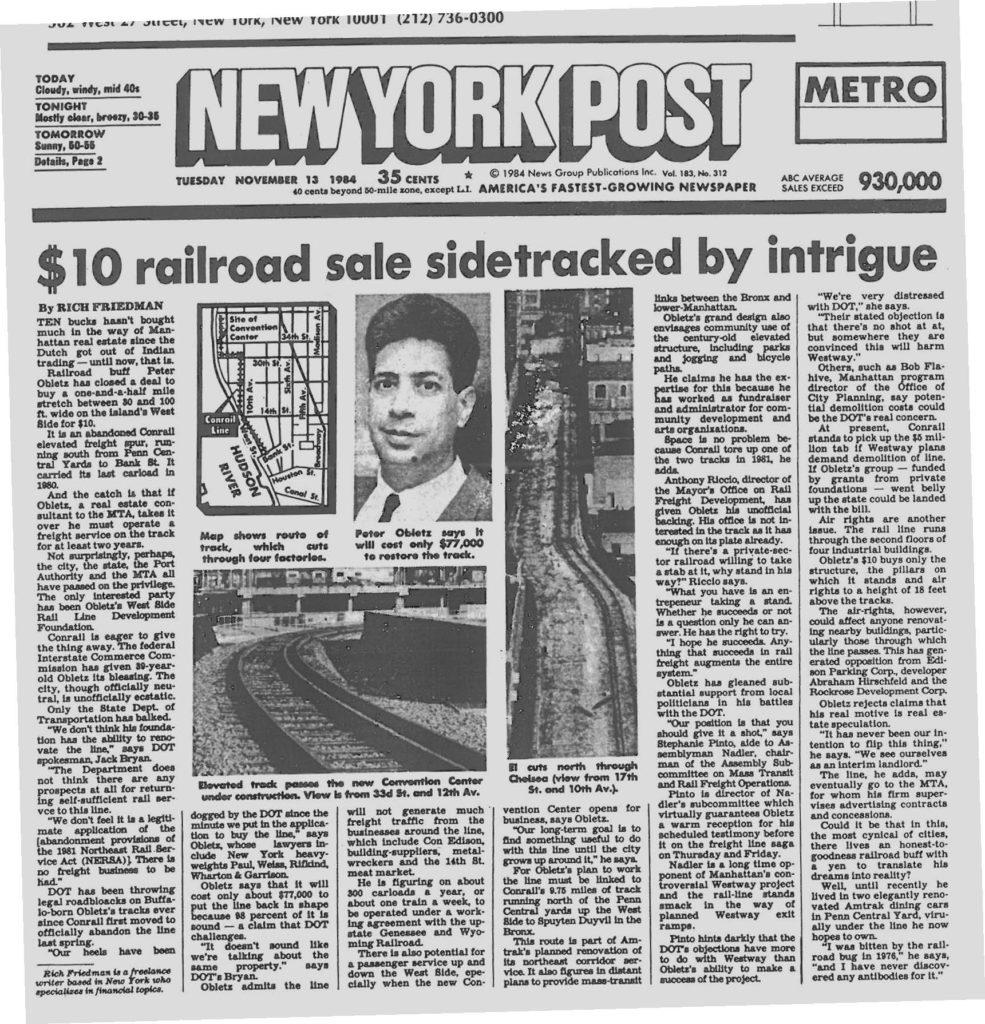

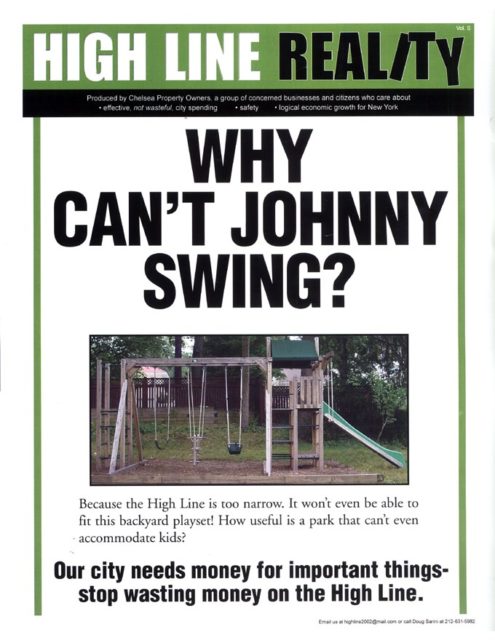

Support for High Line did not come quickly or easily, least of all from the real estate development community. Despite this irony, the High Line has generated over $5 billion in real estate investment and $1.4 billion in tax revenue for NYC over 20 years. This was in large part thanks to the visionary efforts of two private citizens working alongside photographers, benefactors, public officials, and individual citizens to save a doomed elevated railway from demolition by mayoral order and an army of developers that wanted the High Line gone.

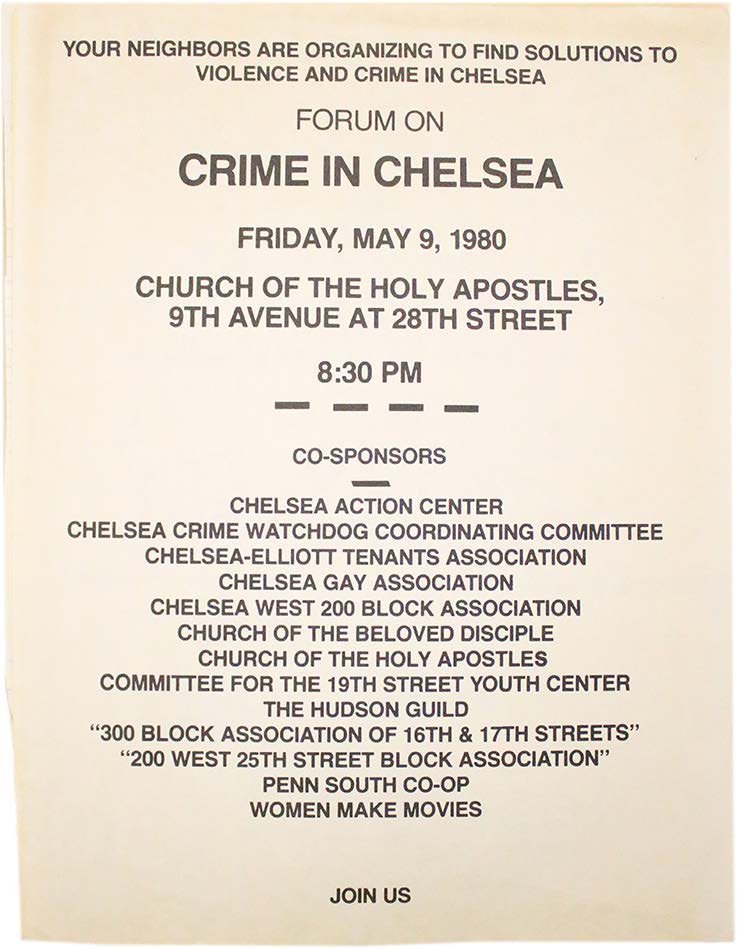

West Chelsea was transforming from a neighborhood of meat–packers, leather clubs, NYC counter–culture, and NYCHA housing projects into one with white collar office workers and developer speculation. The High Line was in the way and had to go. After countless public meetings, fundraising events, celebrity endorsements, guerrilla marketing strategies, and design competitions, Friends of the High Line slowly shifted public opinion from antipathy to enthusiasm. In the process, they even launched a lawsuit against one NYC administration led by Mayor Giuliani before gaining the trust and support of the next administration led by Mayor Bloomberg.

If you were actually able to make a park on the High Line, it would be great for property values. But this will never happen; it is just too far-fetched. These people are dreamers… It’s a pipe dream.

Property Owner at the City Council’s High Line Hearing

Friends of the High Line moved the political reception of the High Line Park idea from negative to positive. While NYC Mayor Guiliani supported demolition, in part because of pressure from local developers, his predecessor, NYC Mayor Bloomberg, saw the High Line as an asset – a unique opportunity to transform the city. For him and other federal, state, and municipal leaders, saving the High Line went from an impossible dream to a ‘no-brainer’.

Developers and property owners aggressively lobbied for demolition of the High Line and against its transformation into a park.

After complex negotiations among property owners, developers, public officials, community groups, benefactors, economists, and designers, the High Line has set a new standard for trans-disciplinary and cross-sectoral coordination in the field of urban design.

The High Line is responsible for record-setting economic development, extensive cultural programming, and the highest standard of excellence in design. More recently though, the High Line has come under criticism, seen by some as an exclusive space for urban elites.

Building the High Line

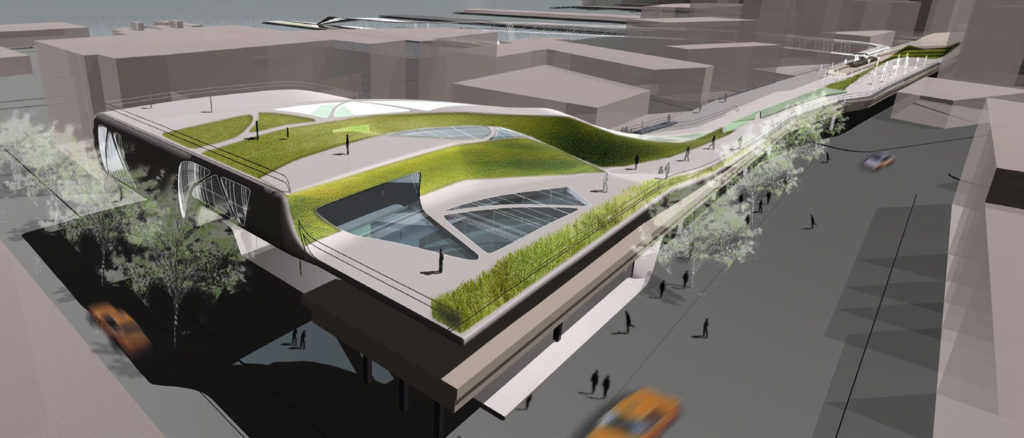

In the early 20th century, construction of the High Line involved threading a modular steel construction system, built to carry heavy freight loads fourteen feet above the ground, through a dense grid of existing buildings and blocks. The challenge of the 21st century was dramatically different, but similarly radical: to adapt an historic structure into an elevated public park. The design and construction of the High Line required coordination between Friends of the High Line, James Corner Field Operations, Diller Scofidio + Renfro, and various levels of government led by the Bloomberg Administration, as well as the cooperation of the development community. Much like in the 1920s, what resulted was a radical vision for the future that went far beyond the known.

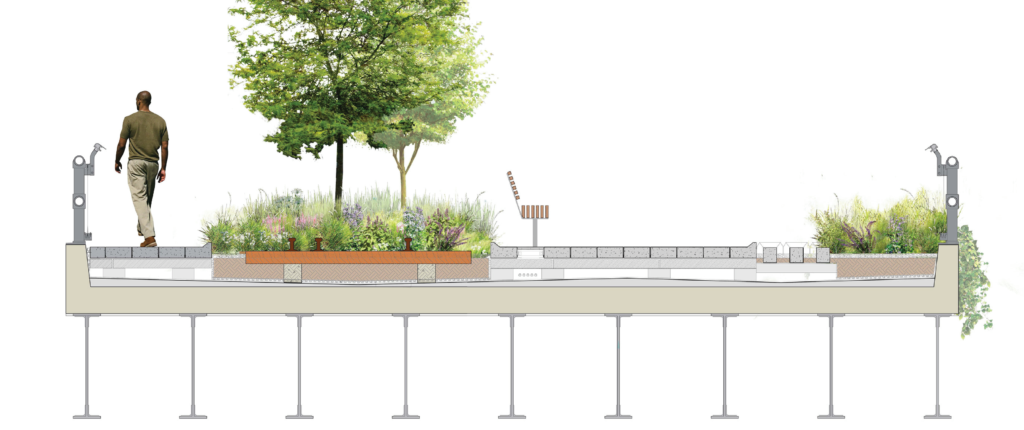

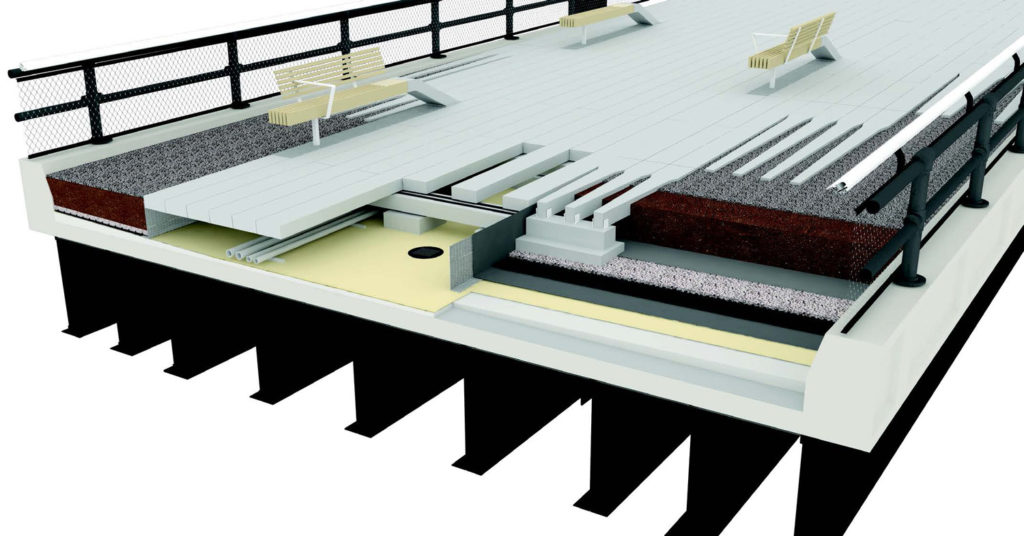

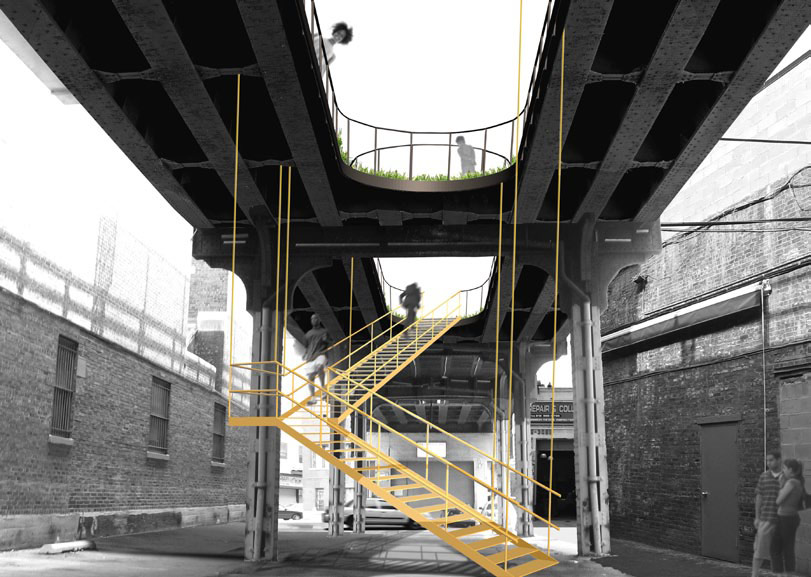

The High Line is a freestanding structure that shifts and moves — something the new design, with its incredibly tight tolerances, had to contend with. The original steel structure was dimensioned to carry freight loads, and while its structural depth was more than sufficient to carry the dead loads of a public park, it only provided, on average, eighteen inches of space in which designers had to fit planking, tree planters, soil, and mechanical, electrical, and drainage systems.

The unique conditions of the High Line presented new challenges for the construction and engineerings firms, including not only hoisting materials thirty feet into the air but also heavy machinery.

All materials and equipment had to be lifted up and down from the structure, often with cranes. Containment tents were constructed to enclose sections of the High Line where lead paint was being sandblasted away. Several deep girders had to be cut both to incorporate new stairs and to provide visual connections to the street. This process had to be carefully analyzed to ensure the remaining structure could withstand projected crowd loads.

Urban Imagery

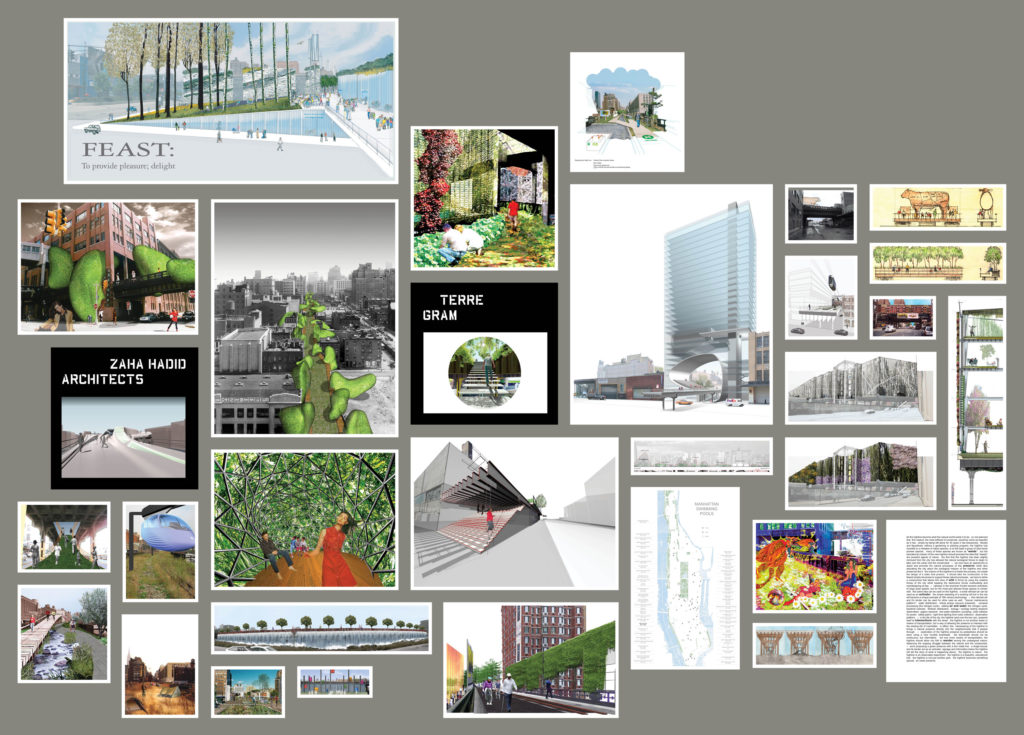

Friends of the High Line were as dedicated to an inclusive public process as they were to design excellence. In 2003, they hosted an open design competition that resulted in 720 entries from thirty-six countries, mostly from students and ordinary people. Notwithstanding their differences, the strongest common thread across all design competition entries was an appreciation for the existing landscape. People loved the High Line for what it had become: an urban wild. The final design team was chosen from fifty-one entries that answered an RFP (request for proposals), asking for a multidisciplinary team. In their presentation, Field Operations and Diller Scofidio + Renfro, were still arguing about the best approach for the project. They were trying to find a balance between preserving the existing wildness and creating something new. For Robert this was summed up on a quote from ‘The Leopard’: “If you want things to stay as they are, things will have to change”.

First we issued an RFQ, a “request for qualifications,” asking firms to join together in teams of architects, landscape architects, planners, designers, and engineers. (…) We received fifty-one entries and narrowed those down to seven, and then we did interviews with those seven designers, to learn how they would approach the High Line. (The High Line: the inside story of New York’s park in the sky)

It can’t be a park like other parks. If it’s like other parks, we’ve failed.

Robert Hammond, Co-founder & Executive Director, Friends of the High Line

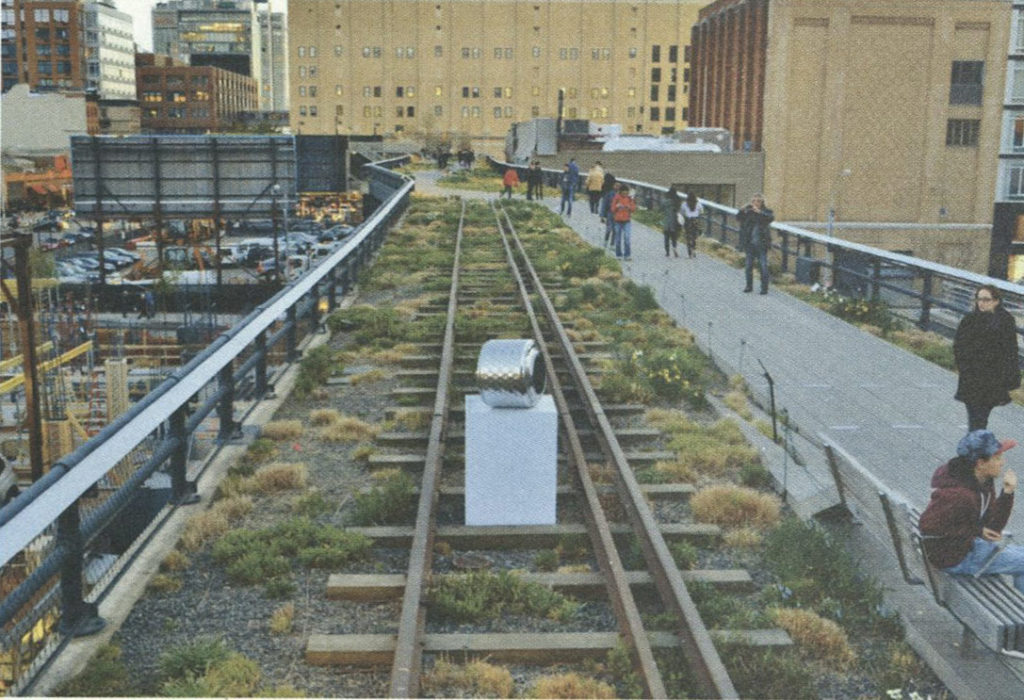

Plants, Planks, & People

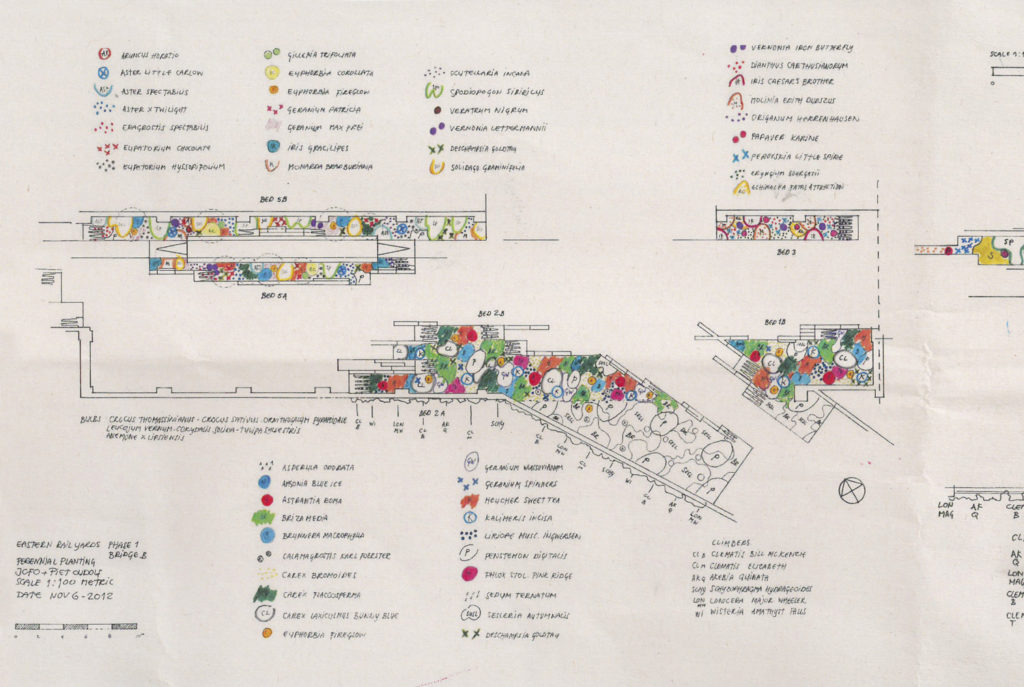

The High Line park was envisioned by James Corner Field Operations, Diller Scofidio + Renfro and Pete Oudolf as a continuous landscape – one that blurs between soft and hard surfaces. The custom planks mediate various material transitions, creating gradients between organic and building materials through a system that is flexible enough to accommodate a wide range of uses while maintaining visual continuity among cultivated, wild, intimate, and hyper-social elements. As a promenade, it is intended to be as slow, quiet, simple, and wild as possible, offering unexpected and exceptional vantages of the surrounding city. Without overly prescribing spaces, the High Line has become a platform for an infinitely wide variety of programs and uses, completely curated by Friends of the High Line.

The melancholic and unruly beauty of the derelict infrastructure was preserved by a landscape design and planting strategy that incorporated a combination of native plants and trans-plants that had colonized the High Line. This created microclimate conditions, responding to varying amounts of sun, shade, water, wind, and shelter. Capitalizing on this diversity of conditions, Piet Oudolf, the planting designer, developed a complex system by mixing dominant grasses with other plants and organizing them so that their color and form punctuate each vista in beautiful and unexpected ways.

A carefully choreographed system of layering, spacing, and repetition create an apparent wilderness that changes continuously throughout the year.

Material Palette

The hardscape materials, benches, and railings are reduced to the essentials: concrete, wood, steel, and glass. The palette is simple and consistent throughout, and its richness is achieved, not by the ostentatious use of materials, but by a flexible system of components that adapts to different uses and enhances the existing railway. The concrete with gravel is used for the planks, the wood for the seating areas, and steel and glass for the railings. The new materials are in direct dialogue with the existing industrial landscape, the signature design aesthetic of the High Line.

A Day in the Life

During the past 40 years, the West Chelsea has undergone dramatic change. While the High Line certainly dominates the present-day character of surrounding neighborhoods, it does so at the expense of many people, industries, and subcultures that had previously ‘made’ the neighborhood. Some local residents, those for whom the High Line park was intended, felt unwelcome and never showed up. Friends of the High Line responded by developing a broad range of initiatives including diversified programming, intentional community outreach, and targeted investments in surrounding neighborhoods. Today the High Line hosts a wide variety of programs—including dance parties, teen internships, and an opera. It is now visited by over 7 million people a year—31% of which come from within NYC.

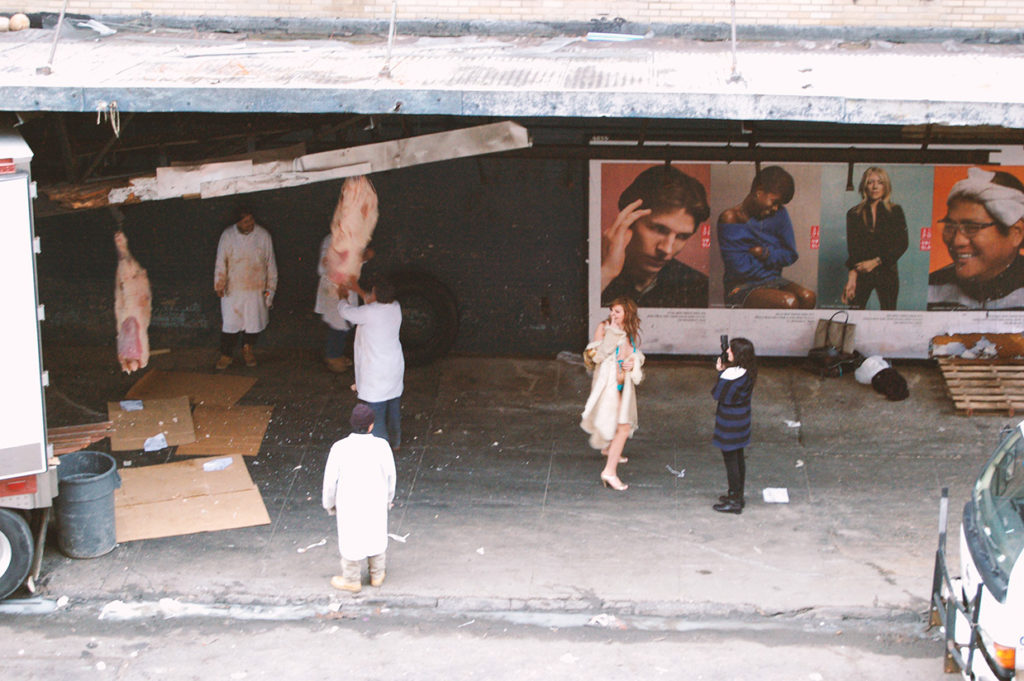

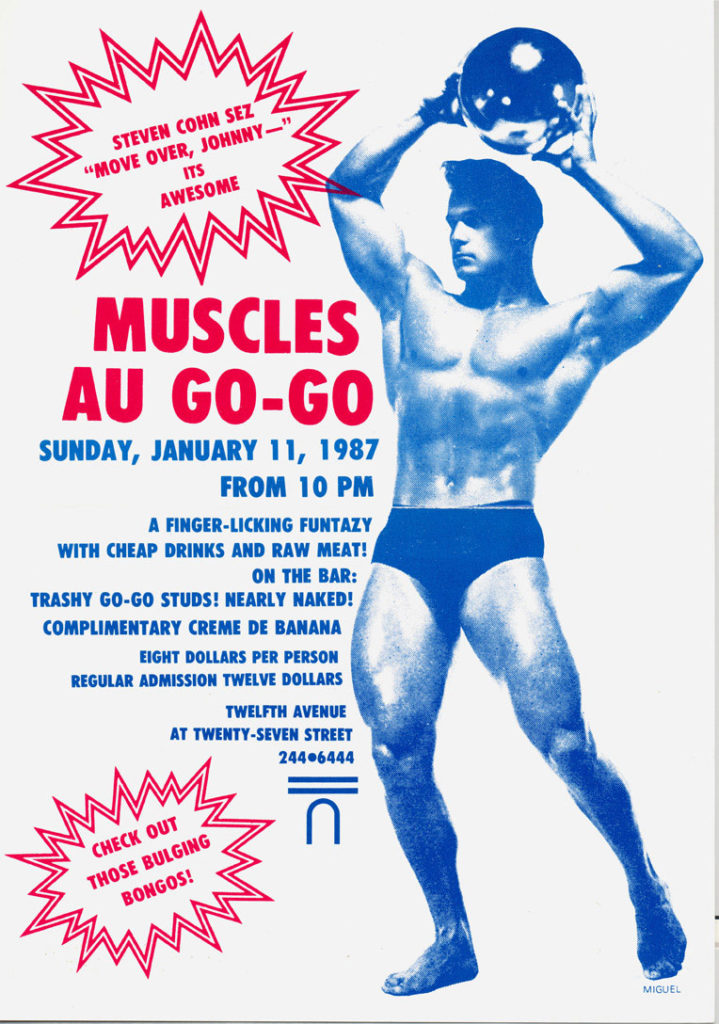

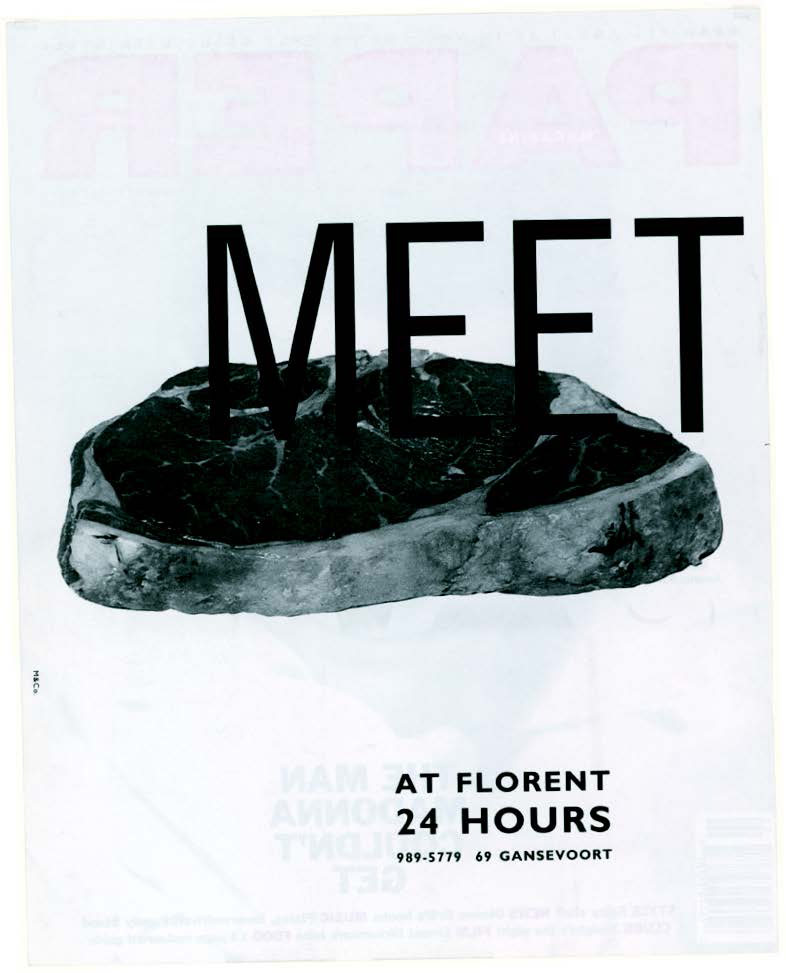

Many of Chelsea mainstays from the 1970s and 80s held on until recently. Meat handlers, sex workers, and gay clubbers shared Chelsea’s streets.

Most manufacturers, many of whom were reliant on the elevated railways, left Manhattan during the economic decline in the 1970s. However, the meatpacking industry remained around 14th Street.

A richly diverse community moved into empty warehouses in Chelsea. In 1985 Florent Morellet took over the R&L Restaurant, which had opened in 1943, and renamed it Florent. The following January, a reporter from New York magazine referred to it as “New York’s hottest downtown eating spot.” The restaurant closed on 2008.

Declining industry in the 1970s left the West Side warehouses empty, the High Line abandoned, and a diverse community marginalized, much of it low-income. This made room for warehouse conversions into clubs and social spaces to support a vibrant and growing gay culture. By the 1980s, during the AIDS epidemic, the neighborhood became a center for activist efforts. Later, with the opening of Dia Center for the Arts in 1987, a gallery scene began to flourish in Chelsea. The occupation of empty warehouses and lofts by artists, priced out of SoHo, accelerated the transformation of West Chelsea to a neighborhood of galleries and lofts. By 2003, West Chelsea had become one of the most fashionable neighborhoods in Manhattan.

Teen Arts and Culture Council offers teens an opportunity to develop skills in cultural production and social justice, and culminates in two events exclusively for teens on the High Line that bring together more than 1,400 teens from all over New York City.

High Society

The High Line Art program curates and commissions world-class art projects on public space. The High Line is the only park in New York that exhibits contemporary art all year round, for free. The art objects engage with the unique structure, provoking an important dialogue with the surrounding neighborhood and the urban landscape.

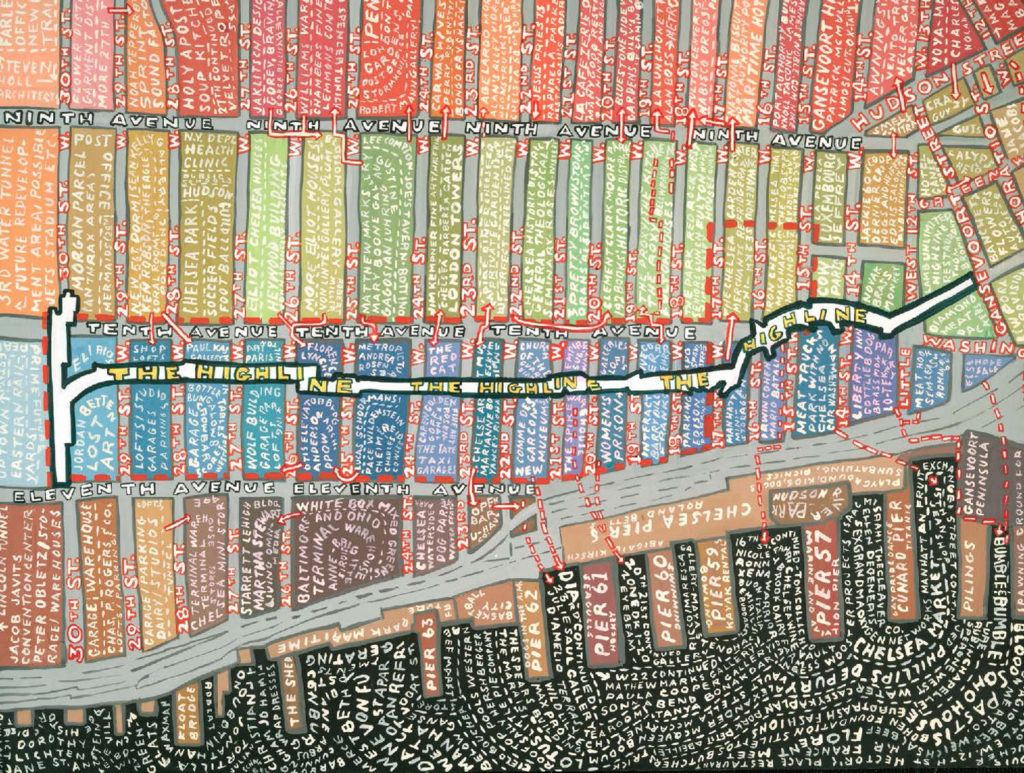

The artist and graphic Paula Scher painted this High Line neighborhood map as part of 2005 series The Maps.

Before Josh and David had an office or employees, they commissioned Paula Scher for their logo.

The opening of the park coincided with the obsession with smartphones. Apps such as Flickr and Instagram reveal the public’s obsession with photographing themselves on the High Line.

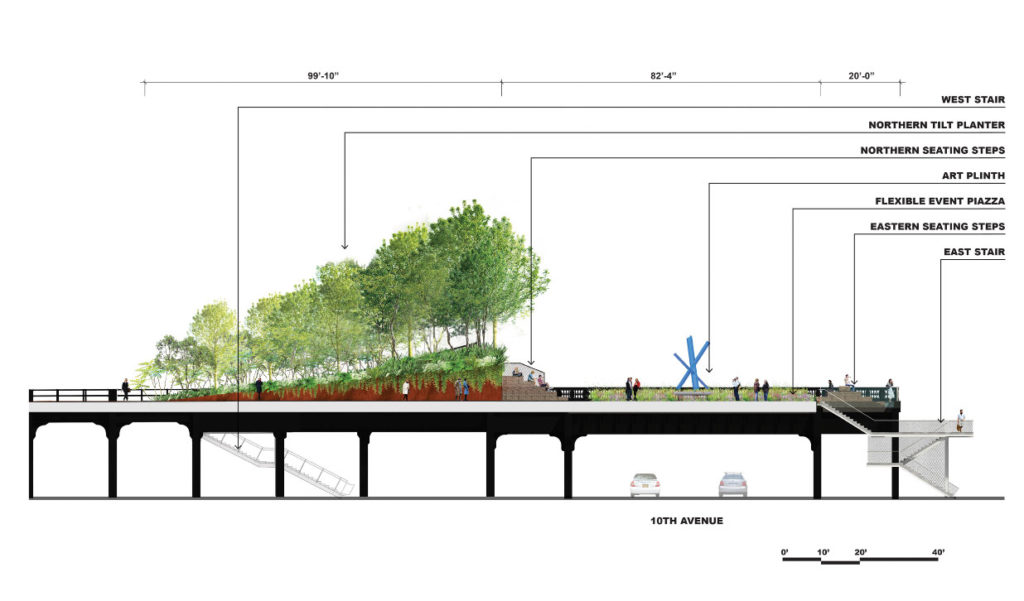

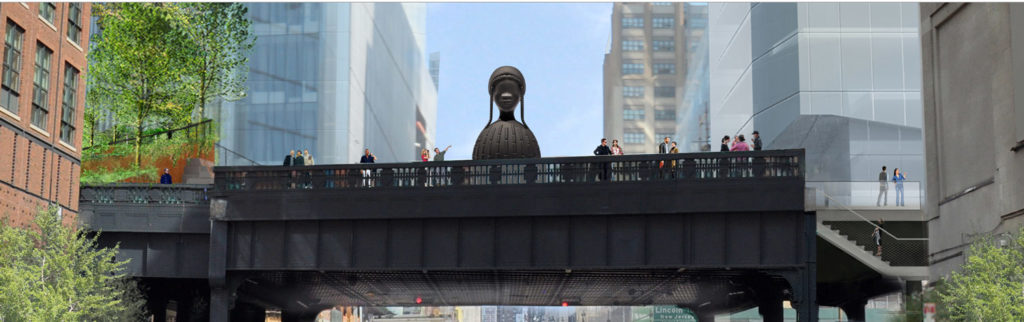

The High Line Plinth is a new landmark destination for major public art commissions in New York City located on the High Line at West 30th Street and 10th Avenue. Designed as the focal point of the Spur, the newest section of the High Line, the High Line Plinth, will designate the first space on the High Line dedicated specifically to art, featuring a rotating program of new commissions.