Porto & Medellín

2013 PRIZE

The 11th Veronica Rudge Green Prize in Urban Design honors two projects that demonstrate the potential for the planning and execution of mobility infrastructure to transform a city and its region through carefully articulated design interventions. Established in 1986, the biennial Green Prize recognizes projects that make an exemplary contribution to the public realm of a city, improve the quality of life in that context, and demonstrate a humane and worthwhile direction for the design of urban environments.

Metro do Porto is a project of significant scale and complexity: 68 km of new track and 60 new stations were designed and constructed in 10 years. The scope of such an undertaking within a UNESCO site and the incredibly high standard of design are breathtaking.

Metro do Porto not only connects residents on the periphery with amenities and services in the historic city, it also forges a collective identity through its negotiation of the region’s unique geography and the composition of individual stations in relation to that geography.

About the Project

Overview

Cities do not change of their own free will or by political decree, but with the emergence of systems that they need to survive. […] It will be thus in the 21st Century by which time the surface light rail system must be integrated into a planned system (enough of improvisation) creating a new urban landscape that cannot be postponed.

Excerpt from A Arquitectura do Metro by Eduardo Souto do Moura

Juror and professor of landscape architecture Gary Hildebrand described the historic center of the city, “Like the phenomena we see in some American cities, there’s a kind of hollowed out core. It’s historic and it’s beautiful, but until this metro project came about, not so vital. The jobs are not in the downtown, and over the last generation people had moved to the boarder reaches.” According to Hildebrand, the introduction of the Metro system was “like reviving the circulation in a human. The center could thrive again.”

Metro do Porto has been a strategically decisive project for shaping the intense demographic change and socio-economic restructuring occurring in the metropolitan area and provides a future template for cohesive and resilient regional change. While mobility plays an important role in achieving these outcomes, the decision to engage the exemplary urban design skills of Eduardo Souto de Moura (Pritzker Prize winner and former GSD visiting professor) underlines the ambitious holistic aims of the project.

Metro do Porto not only connects residents on the periphery with amenities and services in the historic city, it also forges a collective identity through its negotiation of the region’s unique geography and the composition of individual stations in relation to that geography. New stations become opportunities to connect previously segregated neighborhoods within public space rehabilitated to the highest standard. Because of their spatial and material quality, the experience of the stations—as objects within a culturally rich urban landscape and as interior architectures imbued with civic virtues—is exceptional. Metro do Porto exhibits a generosity towards the public realm that is unusual for a contemporary infrastructure project.

A Naturally Artificial Work

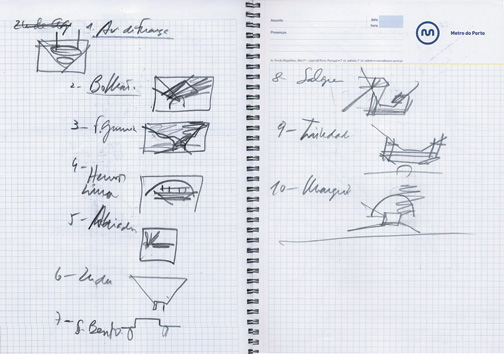

The process to produce the surface light rail network connecting the nine municipalities of Oporto Metropolitan Area began in 1991. At the time the municipalities of Oporto, Gaia, and Matosinhos commissioned a first study from Ensitrans. Between October 1992 and January 1993, a decree of the Portuguese Council of Ministers incorporated the public entreprise “Metro do Porto” to carry out the work. Finally, in 1995 an international rehabilitation tender was launched for the design, construction, supply, and maintenance of the surface light rail system, asking for technical solutions and cost estimates. Three of the four consortia involved in the tender brought in three Oporto architects: Metro Portucalense—Álvaro Siza; Metropor—Alcino Soutinho; and Normetro—Eduardo Souto de Moura. In 1997 Metropor and Normetro were invited to submit the preliminary study with a budget estimate. Normetro was awarded the tender, the agreement was signed in December 1998, and execution began in January 1999. The project comprises four lines: two urban lines on a West-East (Matosinhos–Maia) and North-South (São João–Vila Nova de Gaia) direction, that intersect at Trindade Station, and two suburban lines, Matosinhos–Póvoa and Matosinhos–Trofa. There are almost 70 kilometers of underground and surface track (recovering the existing rail network between Matosinhos and Oporto), equipped with over sixty stations, some of them underground.

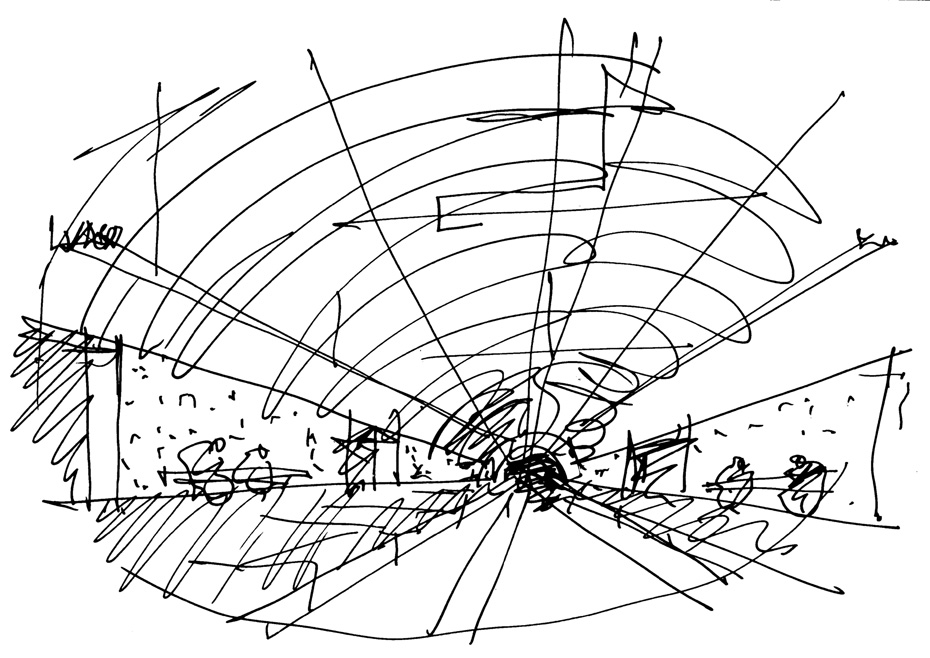

It is difficult to picture the complexity of the metro construction process, which was conceptually developed on many levels, ranging from infrastructures to interior architecture and including, at both extremes, the scales of land use and detailed drawings. As a result of the cooperation of many people, including the architect, who at first sight appeared to have only a marginal role, this operation was achieved. The Normetro consortium, responsible for the operation, is an association of companies with people who have different skills: either general, such as designing and executing the construction work (coordinated by another join venture called Transmetro), or specific, such as relating to track layout and the technical layout of the underground stations. On this occasion, Eduardo Souto de Moura worked “embedded” in the Transmetro technical team, constantly in touch with the engineering company responsible for the underground station concepts concerning modalities and systems of access, security, ventilation, arrangement of spaces, etc. “In this case, there is no point still in discussing that old project/construction versus construction/design dichotomy,” said Souto de Moura about this work. He added that above all he found himself working in a very retricted situation: something that is unusual for most architects, when “materials and techniques today allow us maximum leeway of rules,” but which was fine with him, a “system” in which the idiom is very close to the constructive solution and where “imagination” is above all geared to solving difficulties.

As regards Souto de Moura’s design intervention, it is important to underline the fact that only one designer was foreseen for Porto, different from what happened on the lines of the Lisbon Metro, for instance, where each station was allocated from the start to a different architect. Even so, having been awarded the tender, Souto de Moura also saw his role as coordinator, and so to develop the projects for the stations and the arrangements of the surface layout he involved other Oporto architects: Rogerio Cavaca (Gaia Line), Fernando Távory and Jose Bernardo Távory (Matosinhos Line), Alcino Soutinho (Matosinhos Center), Humberto Vieira (renovating the train stations on the Póvoa a Trofa Lines), Álvaro Siza (São Bento Station, Oporto), João Alvaro Rocha (Maia Line except for the center which was designed by Souto de Moura), Bernardo Ferrao (renovating old train stations on the Trofa Line), Adalberto Dias (São João Hospital Area). When Humberto Vieira and Bernardo Ferrao died, Jose Gigante was invited to join the project of the stations on the Póvoa and Trofa Line. Some of these architects were also involved in projects for urban arrangements in areas through which the metro passed which, according to Souto de Moura, coincided crucially with the aim of harmonizing the different tasks and specifically all works related to the initiatives of Oporto European Culture Capital 2001. During the first discussion and confrontation phases with the Town Council, the Metro project appeared as the opportunity to transform and rehabilitate the areas covered by the stations, by designing new pedestrian routes, pavements, lightning, street furniture, etc. Accordingly, all interventions came under an autonomous project, which was nevertheless integrated in a system of rules studied and controlled by Souto de Moura. The system guaranteed an overall uniform image (while maintaining cost control and high quality standards). This framework of rules was valid for the different types of stations, the surface ones divided into “urban” and “suburban” and the underground stations characterized by greater complexity due to the construction method chosen.

The many sketches, study models, and drawings produced by Souto de Moura and his coworkers on this project help us understand the meaning of many of the statements that appear in the interview, for instance, when the architect defines the Metro stations as “negative” projects, without façades, bodies “on plan and section,” or when he mentions studying a “rule” for the Metro stations. The pictures of the stations, showing the materials used, such as “Spi Alphão” granite for paving, roughcast tiles for the walls, the cartonado plaster of the finishings and false ceilings, the steel and glass for the lifts, doors, and other features, etc., reveal an extremeley high standard of quality for a public work of this type. We believe that allowing Souto de Moura to develop this project shows great vision for the future. In this regard, the intervention of the Porto Metro constitutes an exemplary urban project that shows how, once one has clearly assumed the complex problems, one can reach a “natural” resolution (as required by all representations).

The Metro and the City

by Eduardo Souto de Moura

The surface light rail system glides smoothly over ground on two steel rails, making hardly any sound.

The laying of the track is dictated by a closed circuit elevation value system complying with strict rules that have no subjective considerations. The steel rails must be full embedded in the street pavement so that, in the event of an emergency fire, service vehicles can pass from one side of the track to the other. The material used ranges from granite cubes to bituminous pavements or grass covering.

For acoustic reasons the rails are laid on a floating slab using steel components cushioned with rubber dampers.

The installation of the system meant that whole streets had to be destroyed and, as a result, their infrastructures also.

New sewage, rainwater, gas, electricity, telephone, cable TV, optic fibre cables and even oil pipe pipeline distribution networks have to coexist with the Metro light rail system being built—which is achieved with multi-transport pipelines with access points every 20 metres.

But the problem of the surface metro does not exist only on the surface.

There is also the sky to consider—the catenary and the lighting systems. These can be suspended from a central post or from two lateral posts.

When the street are too narrow the catenaries and lighting are suspended from cables that are stretched from one building front to the other. The problem is that such facades are either made of “NUAGE” glass or have a 7 cm-thick brick outer wall.

We work from the track outwards to the sides of the roads (the Metro track is always inflexible). Any space left over on the street is given over to other vehicles and parking where possible, and pedestrian pavement until the stoops are reached.

We can alternate materials and modify inclinations but the building stoops are “sacred,” it is like touching a stranger on his shoulder. From shoulder to shoulder we modify elevation values, pavements, textures, pathways, road kerbsides, kerbstones, lamp-posts and trees. lt is not that we want to alter the geography but ‘Metro oblige.’

When difficulties arise we speak to Transmetro or to Normetro, which then speak to the Metro, the town council, the parish council, the residents, and the tradesmen.

After being approved, we being to see streets that intersect and widen into squares, plazas, roundabouts, superfluous recesses, small courts, tree-lined plazas, parking on roadsides, and even boulevards—Avenida da Republica: Gaia I Matosinhos.

Although this is not our vocation the Metro system builds places, nooks, joins cities, designs metropolises—Gaia, Porta, Matosinhos, Maia, Trofa, Vila do Conde, P6voa de Varzim and Gondomar.

Cities do not change of their own free will or by political decree but with the emergence of systems that they need to survive and develop.

It was thus with the Romans when at the crossroads of two routes they designed the Cardus and the Decomanus with the Forum in the centre. lt was thus in the Middle Ages when the Forum was replaced by Cathedral Square, built with the stones of the demolished temple.

It was thus in Baroque times with radiocentric axes connecting that Cathedral (now filled with gilt wood carvings) to the city gates.

It was thus in neo-classical times when the gates were demolished or redesigned and the spaces where the roads ended became squares flanked by convents. lt was thus in the 19th century with the railroad, when some convents became stations (Sao Bento).

It was thus in the 20th century with the surface light rail system (Matosinhos I Trindade).

It will be thus in the 21st century by which time the surface light rail system must be integrated into a planned system (enough of improvisations).

Creating a new urban landscape that cannot be postponed.

The Northeastern Urban Integration Project in Medellín, Colombia, was sponsored by the City of Medellín, which receives the award for its vision and ongoing support of this project. The prize also acknowledges the design leadership of Architect Alejandro Echeverri and the role of the agency Empresa de Desarrollo Urbano (EDU) in the design, management, and execution of the project.

Working with the community to conceptualize, develop, and construct new open-space networks, the designers of the PUI have sensitively integrated a mobility infrastructure of the strategic goals of large and socially complex projects by developing processes that promote ownership by the community.

About the Project

Overview

Our traditional education is not designed to understand complex thought: each discipline jealously strives to protect its boundaries when, paradoxically, the problems we face demand a structural change in the way we tackle them.

Excerpt from Medellin: Environment, Urbanism and Society by Alejandro Echeverri Restrepo

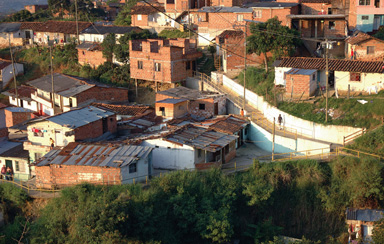

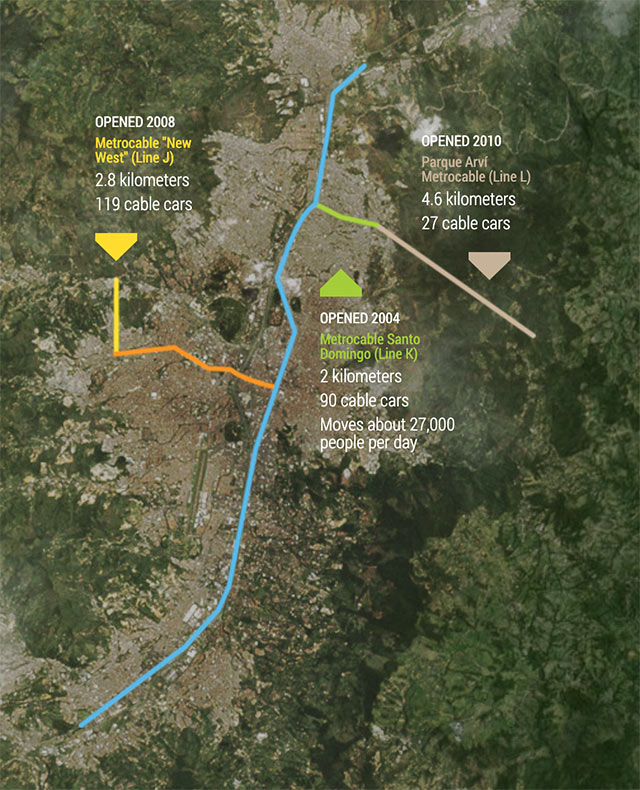

The Northeastern Urban Integration Project in Medellín (Proyecto Urbano Integral, or PUI) was initiated by the City of Medellín in 2004 to harness opportunities presented by the MetroCable, a new cable-car project connecting three informal settlements to the metropolitan transit system. In concert with the MetroCable, the PUI has made a significant contribution toward improving the quality of life for approximately 170,000 residents experiencing severe social inequality, poverty, and violence.

The PUI leverages the economic benefits of new mobility infrastructure to incorporate marginalized communities into the city. By reducing travel times to the city center from over an hour to less than ten minutes, the MetroCable has enhanced access to employment opportunities and eroded the boundary between the formal and informal city.

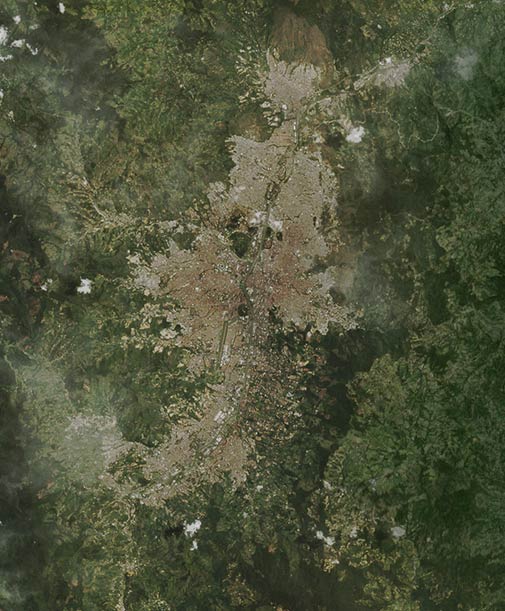

Medellín is located in the Aburrá Valley in the central Andes, 1,479 meters above sea level. Known as the “City of Everlasting Spring,” it has only recently become a metropolis. It is the second-largest city in Colombia (after Bogotá) and the capital of the department of Antioquia. From 1938 to 2008, the population of Medellín increased from 168,000 to 2.34 million. This population skews relatively young, with almost 70 percent between five and forty-four years old.

Ninety percent of the population lives in about 30 percent of the city’s territory. Medellín is divided into 249 neighborhoods (barrios), 16 communes, and 6 zones. Of about 600,000 housing units, 77 percent are occupied by those at the lowest socioeconomic levels, while 19 percent house those in the middle and upper-middle levels. Four percent of the housing units are home to those at the highest economic level.

The city generates more than 8 percent of Colombia’s GDP, with the Aburrá Valley as a whole contributing close to 11 percent. Surpassing that of the other major cities of Colombia, the GDP per capita (with purchasing power parity) is U.S. $3,794; and corporate density is 25 companies per 1,000 people—the second highest in the country. Although Medellín was once known as “The Industrial City of Colombia,” global and national economic dynamics have shifted the city’s focus to Medellín shares the Aburrá Valley with nine other municipalities, which collectively create a metropolitan urban area with a population of 3.5 million people.

Marginality in Medellín

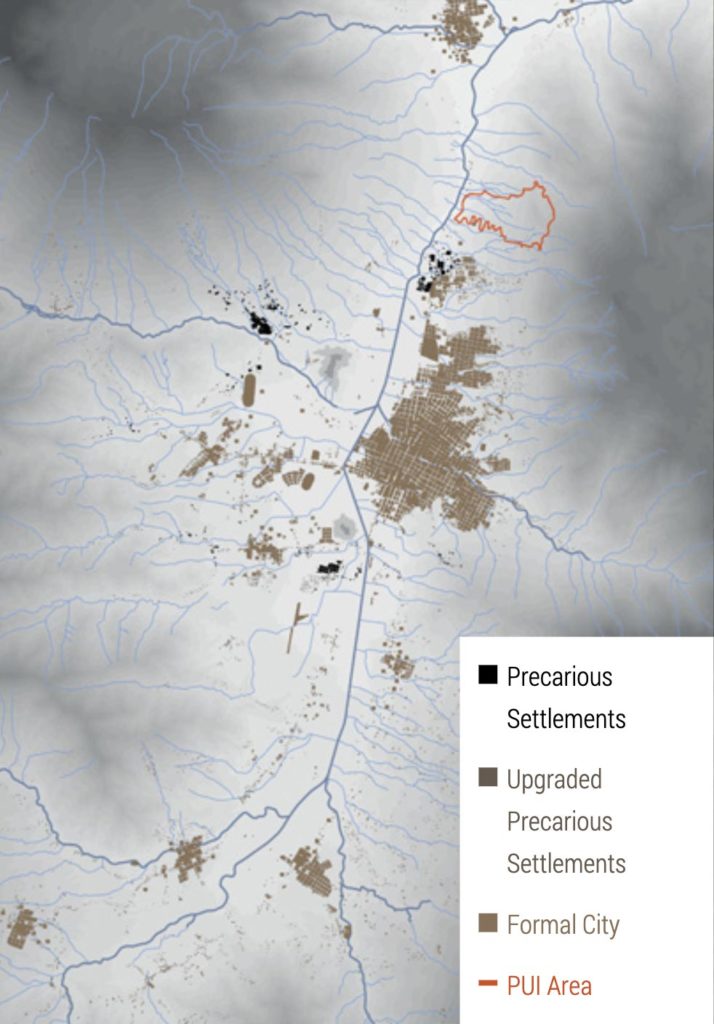

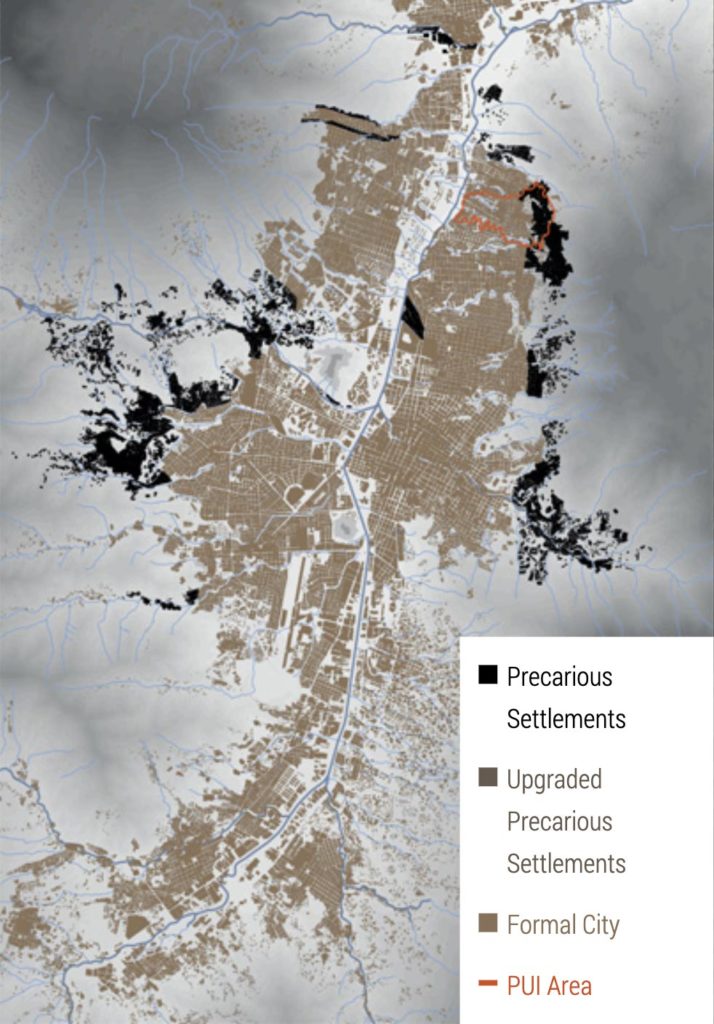

The process of “informalization,” understood as the formation of precarious neighborhoods, has been a characteristic of Medellín’s history throughout the twentieth and into the twenty-first century, a consequence of the continuous migration toward the city.

The effects of this demographic growth became evident at the beginning of the last century, in the considerable rise in the demand for housing. This heightened demand was associated with the production of working-class residences for the huge numbers of manual laborers needed in the emerging industrial sector.1 From that time on, neighborhoods created through both public and private initiatives began appearing, primarily near the northeastern bank and along the tram route and principal roads. The public residences were the product of institutions such as the Instituto Crédito Territorial and the Banco Central Hipotecario, while the private residences represent investments by local landowners.

Despite these significant public and private efforts, the demand for housing continued to grow in the following decades. A migratory wave following the rural displacement and political violence of the 1950s pushed the city’s annual growth rate to 6 percent.

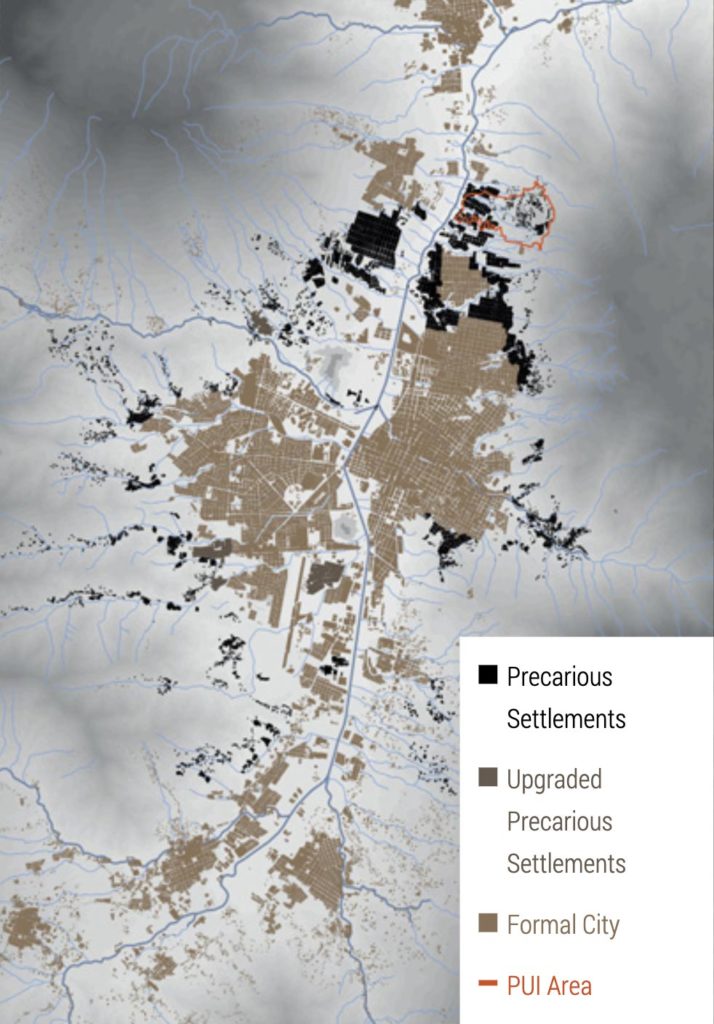

In ten years Medellín doubled its population; informal squatter settlements (urbanizaciones piratas) and illegal neighborhoods (barrios de invasión) began to appear in the most inaccessible peripheral areas. From this period we find the examples of Popular, Santo Domingo, and Granizal toward the eastern bank, and Doce de Octubre and Picacho toward the western bank.

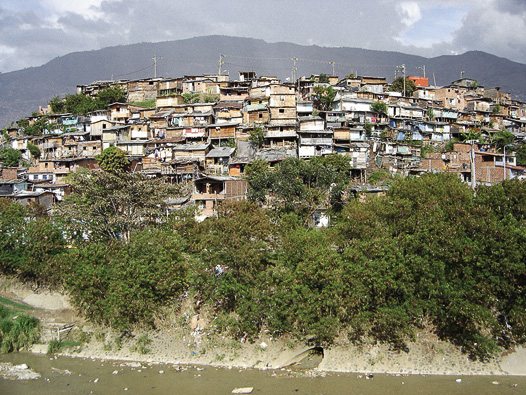

Increasing in intensity, the new urbanizing dynamic began to generate profound segregation within the city’s physical, social, and economic western slopes, the informal city began to emerge; here one finds the ad hoc residences of the poor. Parallel to these areas, the middle and upper classes occupy the center and south of the valley, in the planned formal city. Medellín’s path diverged into two realities—two opposing “cities”—dramatically segregated by location and geographical relief.

Thirty years later, a new wave of violence and rural displacement, combined with emerging narcotics trafficking, drove informalization in dramatic political and social directions. The neighborhoods of the northern slopes of the valley, commonly termed “comunas,” became the habitat of illegal gangs—bands of assassins who acted on the orders of narcotics traffickers and other criminals. State control and presence in these sectors was almost nonexistent. As a result of informalization, 25 percent of Medellín’s territory (a total of 2,400 hectares) now lies in marginal neighborhoods.

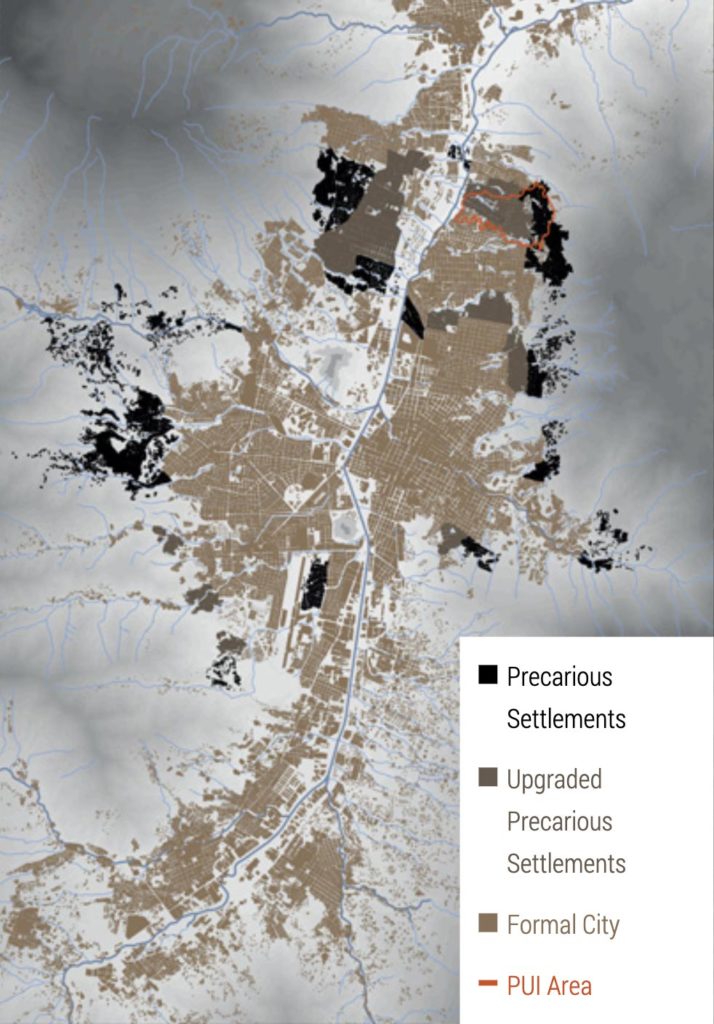

The public administration, along with academic and other nongovernmental organizations, has been trying to address decades of inequality by implementing programs aimed at transforming the quality of life for the inhabitants of marginal neighborhoods. Many difficulties of the informal city—inequality, violence, and segregation—were an inherent aspect of its past. Although they remain challenges of the present, there is a move toward change so that they will not be part of the future of Medellín.

Social Urbanism

Under the leadership of Mayor Sergio Fajardo in 2004, the city bet on a public policy focused on reducing the profound social debts that had accumulated over decades, in addition to the legacy of violence. To address these problems, structural transformations that combined programs of education, culture, and entrepreneurship were implemented. Neighborhoods located in the most critical zones of the city were given special attention; for the transformation of the comunas, this involved social urbanism and urban projects that drew on the best technical knowledge and designs.

The strategic urban projects that were defined as priorities in the municipality’s development plan (Library-Parks, the Schools of Quality, the City Center Plan, the Poblado Plan, the projects for “a New North,” and the Integral Urban Projects, as well as others) were sponsored by Medellín’s Empresa de Desarrollo Urbano (EDU), a decentralized entity founded in 1993 as part of the city’s municipal structure.

The EDU experienced an internal transformation as specialized interdisciplinary teams dedicated to each of the strategic urban projects were set up, becoming vital instruments that planned and executed urban projects in the prioritized territories. Each strategic project had a manager responsible for creating channels of communication and coordinating relations between the various actors and institutions.

The EDU assumed sole technical leadership over this exclusive group of projects and territories. Some of the keys to success were the political leadership and inter-institutional coordination. Teaming with the city’s planning office and rigorously monitoring all of the internal processes of administration and execution enabled, in only a few years, the completion of a wide range of highly complex projects.

Mobility

The most significant event in the establishment of improved mobility within the Aburrá Valley was the establishment of the Metro in 1995. With 31 kilometers of track, it is (with the Metro of Santiago, Chile) one of the most efficient in Latin America. The Metro’s speed is 37 kilometers per hour, while the cable-car system Metrocable’s is 18 km/hour, and city buses run at speeds of about 15 km/hour. In 2006, the Metro released the master plan for 2006–2020, entitled “Trust in the Future.” Several expansion projects were subsequently evaluated, including new cable-car systems, trams along 80th Avenue and Ayacucho Street, and the extension of Line B to the east.

Integral Urban Project Methodology

The Proyecto Urbano Integral (PUI)/Integral Urban Project is an instrument for planning and physical intervention in areas characterized by a high degree of marginalization, segregation, poverty, and violence. PUIs are targeted to solve specific problems in a territory where the state has generally been absent.

The Integral Urban Project strives to integrate community participation, inter-institutional coordination, promotion of housing, and the improvement of public space and mobility. In addition, the PUI promotes support for collective amenities and the restoration of the environment.

With these criteria, the northeastern communities of Medellín provided a fitting test for the pilot project. These sectors of the city had the lowest ratings on the quality-of-life index and index of human development. At the same time, in the same area, there was the launch of the Metrocable, a system of transportation that connected these informal settlements to the city Metro system by cable car. The PUI helped to select the location of the stations, with the objective of complementing and amplifying the positive impact of the Metrocable.

The PUI implemented a process of neighborhood consolidation through a series of projects that generated both increased accessibility and greater structure in the region. These projects were characterized by community amenities—parks, streets, walkways, and pedestrian bridges that connected neighborhoods. The PUI northeast is focused on improving public infrastructure as a means of social transformation, primarily in the densely populated areas of the city that formed in the 1950s, largely through extralegal urbanization.

The methodology applied in the northeastern PUI was gradually developed during the project. This method is similar to those used in comparable projects: first comes identification of the issues, next a diagnosis, and then a formulation of strategies to solve or minimize the problems. In addition to the high degree of institutional coordination, this project was innovative because of its sustainability phase; this phase began parallel with the intervention and continues after it, involving the community as an active part of the process from the start.

PUI Components

Although the PUIs’ physical, social, and institutional initiatives are effective, preventive security and development management cannot be viewed as the complete answer. Instead they are useful tools to enhance and rebuild a culture of citizenship. This in turn gives rise to co-responsibility, solidarity, awareness of both duties and rights, and the return of positive urban dynamics destroyed by decades of social exclusion. In short, proper planning can be a pivotal tool to confront and prevent violence.

Physical: Based on urban interventions and strengthened by community participation. Includes the construction and improvement of public spaces, housing, and public buildings, and restoration of the environment.

Social: Relying on a strategy of identifying problems and opportunities, establishing and approving projects, and using participatory design practices such as public workshops. Combined with strengthened community organization and leadership promotion, this allows for restoration of the social fabric.

Institutional: Involving the coordination of activities carried out by all elements of the municipality in a particular zone. In addition, alliances with the private sector, NGOs, national and international bodies, and community organizations are promoted.